Why do we even have CORS? If you wish we could just turn it off and forget it ever happened, you wouldn’t be alone. Luckily, once you understand what it protects against it’s pretty painless to avoid.

Why CORS exists

When your browser requests an page from a server, it sends along all the cookies that server has asked it to keep track of. This is how I can visit gmail.com and see my email instead of yours—my browser sends along a cookie that gmail uses to know which account is logged in. As much as cookies and tracking get bad press, they’re an essential part of the web.

This poses a potential security risk though. What if I operate the viral cute-pet-pics.net site and decide to commit a crime with a computer? I could write javascript to execute a request to bank.com/account-numbers from every visitor’s browser. For anyone who happened to be logged into their bank.com account, this request would include the cookies that track their logged in account. Some requests would fail, when a user wasn’t logged in or didn’t have a bank.com account, but I could save any successful responses to my own server.

To prevent this, requests initiated from javascript (and a few other contexts) have CORS restrictions. The server has to send an explicit header indicating to the browser that it’s okay for javascript on other domains to see the server’s data. If the server opts in and says “anyone can see this stuff”, the browser will let you access it.

What to do about it

If you have control over the server where you’re requesting resources, you can add the appropriate headers to opt-in to cross origin requests. For example, here are some instructions for a node express server (from zigpoll.com)

app.use((req, res, next) => {

res.header('Access-Control-Allow-Origin', req.headers.origin);

res.header('Access-Control-Allow-Credentials', true);

res.header('Access-Control-Allow-Headers', 'Origin, X-Requested-With, Content-Type, Accept');

next();

});

If you don’t have control of the server, the best option is to make your own server that proxies to it. That is, stand up a server to perform the request for you and tack on the CORS headers.

For example, the incredibly useful duck API at https://random-d.uk does not currently include CORS headers. We can’t hit it directly from the browser. So let’s set up a proxy to

- Accept requests at a URL we own and forward them to random-d.uk

- Once random-d.uk responds, tack on some Access-Control-Allow-Origin magic

- The browser will see the new Access-Control header, and our JS code gets to see the response.

That’s a little involved, and can be intimidating. I’ve set up a repo that takes care of all the details: https://github.com/bgschiller/cloudfront-cors-proxy. You specify the url of the API and it will generate a proxy with CORS headers.

$ npm run cdk -- deploy --all

...

... lots of output and a couple of security prompts.

...

✅ cors-proxy-random-duck

Outputs:

cors-proxy-random-duck.distributionid = E1SFFWMM5DG8ZF

cors-proxy-random-duck.domainname = d1vhuvp492i00h.cloudfront.net

cors-proxy-random-duck.message = Access random-d.uk without CORS restrictions using d1vhuvp492i00h.cloudfront.net as a proxy

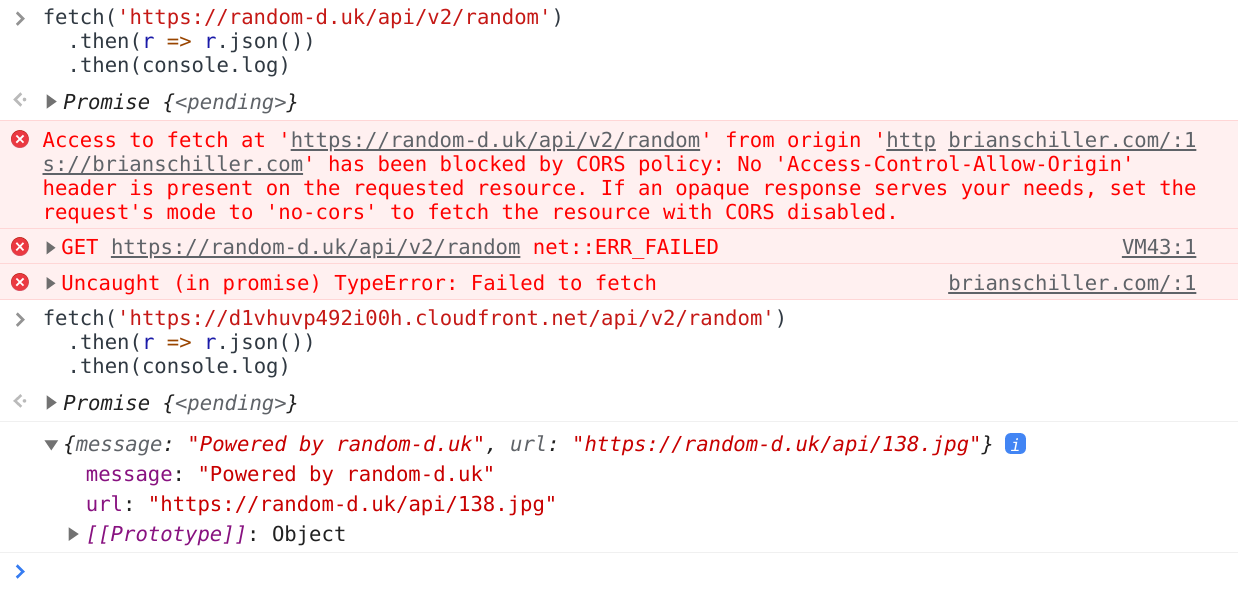

And we can try it out in a browser to see it working. This screenshot shows browser logs listing CORS errors when requesting random-d.uk directly, but a successful request when using the cloudfront proxy.

References

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/43262121/trying-to-use-fetch-and-pass-in-mode-no-cors

- https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/CORS