School starts soon at my alma mater, WWU. For me, Fall quarter always meant I would be taking the Putnam Exam, regarded as one of the most difficult (or the most difficult) math competitions for undergraduates. It consists of two three-hour sessions with six problems each. Most years, the median score on the exam is zero out of 120 points.

The first year I sat the exam, in 2010, this was one of the problems:

There are 2010 boxes labeled B1, B2, …, B2010 and 2010n balls have been distributed among them, for some positive integer n. You may redistribute the balls by a sequence of moves, each of which consists of choosing an i and moving exactly i balls from box Bi into any one other box. For which values of n is it possible to reach the distribution with exactly n balls in each box, regardless of the initial distribution of balls?

Break it down

Whew, what a mouthful! Let’s break that into pieces.

There are 2010 boxes labeled B1, B2, …, B2010

So far, so good.

… and 2010n balls have been distributed among them, for some positive integer n.

Okay, so if n is 2, for example, there are 4020 balls. And all the balls are in some box or other.

”My game’s got a basketball, a football, a kickball, and a tetherball: it’s got all the balls. So I call it ‘All The Balls’. You get it?” -Lawson

You may redistribute the balls by a sequence of moves,

That sounds good to me. What are the moves?

each of which consists of choosing an i and moving exactly i balls from box Bi into any one other box.

So I could take 3 balls out of box B_3 and put them in box B_5. But if I wanted to take balls out of box B_5, I’d have to take them out 5 at a time. And I can do this as many times as I want.

For which values of n is it possible to reach the distribution with exactly n balls in each box,

We’re looking to divide the 2010n balls evenly among all the boxes, but maybe it doesn’t work for every n?

regardless of the initial distribution of balls?

Okay, so my worst enemy could be stacking the deck against me, setting things up so in the worst way they know how, and I still have to be able to evenly distribute the balls.

A smaller version of the same problem

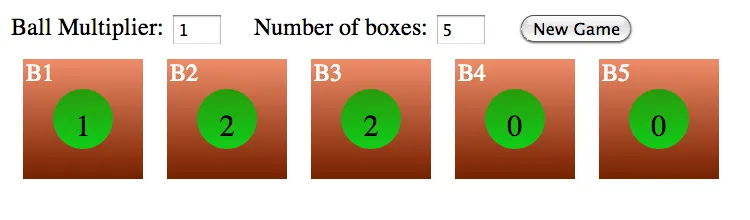

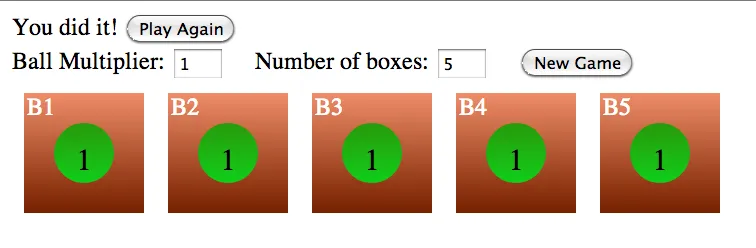

It’s a little hard to visualize 2010 boxes, so lets go with something smaller. How about five? Play with the demo below for a bit. You can move i balls from box Bi by dragging them to another box. Can you get all of the balls distributed evenly? If so, try making it harder by lowering the ‘Ball Multiplier’ (that’s the n from the 5n balls we’re working with).

If you played that for a bit, you probably developed some sort of strategy. (If you didn’t, go ahead; we’ll wait).

Rescue missions

For me, a strategy that seems to work is to move balls towards box B_1, and redistribute from there one at a time. We can also use the balls in box B_1 to ‘rescue’ balls in another box. This is most easily understood with an example.

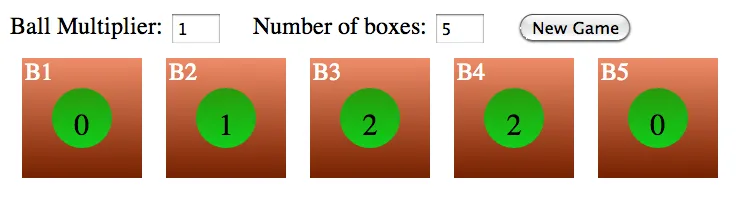

How are we going to get a ball out of box B3?

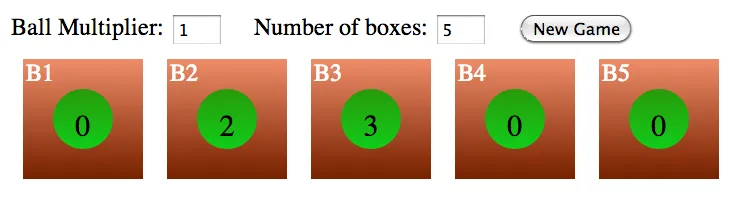

In the game above, our n is 1, so we’re trying to get 1 ball in each box. Box B_3, with two balls, has too many! We need to take one out, but the rules are that we have to take out 3 at a time. So, we will send a ball to ‘rescue’ the balls in B_3.

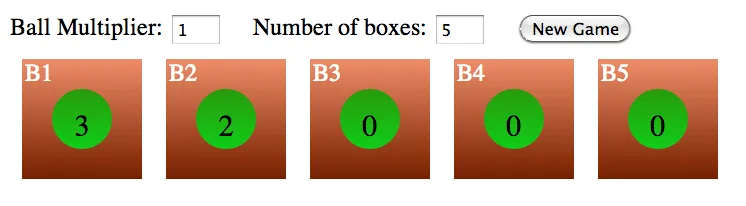

We moved a ball from B1 to B3. Now we have enough in B 3 to move them all to B1.

We move the balls from boxes B2 and B3 into B 1.

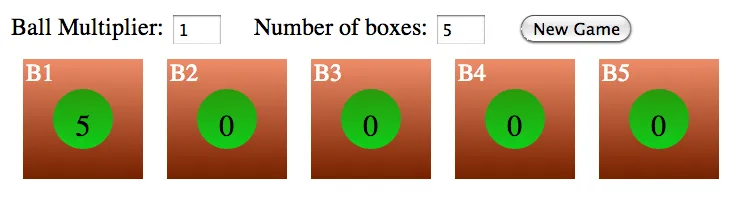

Now that we can move the balls individually, we evenly distribute them.

Okay, so everything’s peachy then, right? Not so fast. Are we always going to be able to execute a rescue mission like that? What could go wrong? I’ll leave you to contemplate that while I admire this orange.

A wrench in the works

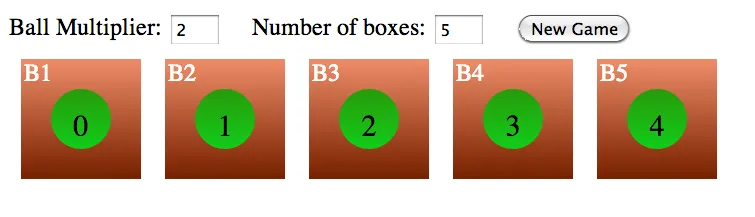

What if everyone needs a rescue, and no one is there to help? Box B_1 has 0 balls, B_2 has fewer than 2, B_3 has fewer than 3, and so on.

Nobody here is planning on moving before the spring thaw.

What can we do about this? Well, we could make sure that there are so many balls that this never happens. For this, it is helpful to think of a worst-case scenario. In the very worst case, with the most stuck balls, every box Bi has i -1 balls. There is no slack anywhere in the system.

Every box has one ball too few to be able to move them.

In the 5 boxes case, the worst-case scenario involves 10 balls: 0 + 1 + 2 + 3 + 4. We know that if the game comes to us in that state, we’ll never get the balls evenly distributed. But if there’s even one more ball, everything frees up. Wherever that extra ball lands, we can move the balls in that box into B1, and from there execute rescue missions.

How many balls do we need for 2010 boxes? We still need one more than worst case of 0 + 1 + 2 + 3 + … + 2009 , but what is that sum? It turns out there’s an easy way to count up all the numbers from 1 to 2009 (or really anything you like).

How to count

Again, let’s work with a smaller version of the problem. Let’s add up the numbers from 1 to 10.

1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 + 7 + 8 + 9 + 10

Now, add another row below it, but reversed.

1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 + 7 + 8 + 9 + 10

10 + 9 + 8 + 7 + 6 + 5 + 4 + 3 + 2 + 1

Each column sums to 11!

1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 + 7 + 8 + 9 + 10

10 + 9 + 8 + 7 + 6 + 5 + 4 + 3 + 2 + 1

-----------------------------------------------

11 + 11 + 11 + 11 + 11 + 11 + 11 + 11 + 11 + 11

Since there are 10 columns, we have 11 _ 10. But we needed two rows of 1 + 2 + … + 10 to get to that, so we have to cut our 11 _ 10 in half:

Now, to get 1 + 2 + 3 + … + 2009 , we can imagine lining up our rows and sum each column.

1 + 2 + ... + 2008 + 2009

2009 + 2008 + ... + 2 + 1

-------------------------------

2010 + 2010 + ... + 2010 + 2010

So now we can say with surety, the greatest number of balls you can have where it’s still possible to get stuck is

Wrapping up

We now know how many balls we need to have. But if you remember back, the question asked “For which values of n” is it possible to rearrange the balls. So we have 2010n balls, and we need 2010n > 2019045 . Dividing both sides by 2010, we get n > 1004.5. If n has to be an integer (we can’t put 1004 and one half balls in each box!), we get n ≥ 1005.

So there you have it. The only values of n for which it is possible to reach the distribution with exactly n balls in each of 2010 boxes are n ≥ 1005. In case anyone asks.