Also published on AWS Advent

If you’re deploying a traditional server-rendered web app, it makes sense to host static files on the same machine. The HTML, being server-rendered, will have to be served there, and it is simple and easy to serve css, javascript, and other assets from the same domain.

When you’re deploying a single-page web app (or SPA), the best choice is less obvious. A SPA consists of a collection of static files, as opposed to server-rendered files that might change depending on the requester’s identity, logged-in state, etc. The files may still change when a new version is deployed, but not for every request.

In a single-page web app, you might access several APIs on different domains, or a single API might serve multiple SPAs. Imagine you want to have the main site at mysite.com and some admin views at admin.mysite.com, both talking to api.mysite.com.

Problems with S3 as a static site host

S3 is a good option for serving the static files of a SPA, but it’s not perfect. It doesn’t support SSL—a requirement for any serious website in 2018. There are a couple other deficiencies that you may encounter, namely client-side routing and CORS headaches.

Client-side routing

Most SPA frameworks rely on client-side routing. With client-side routing, every path should receive the content for index.html, and the specific “page” to show is determined on the client. It’s possible to configure this to use the fragment portion of the url, giving routes like /#!/login and /#!/users/253/profile. These “hashbang” routes are trivially supported by S3: the fragment portion of a URL is not interpreted as a filename. S3 just serves the content for /, or index.html, just like we wanted.

However, many developers prefer to use client-side routers in “history” mode (aka “push-state” or “HTML5” mode). In history mode, routes omit that #! portion and look like /login and /users/253/profile. This is usually done for SEO reasons, or just for aesthetics. Regardless, it doesn’t work with S3 at all. From S3’s perspective, those look like totally different files. It will fruitlessly search your bucket for files called /login or /users/253/profile. Your users will see 404 errors instead of lovingly crafted pages.

CORS headaches

Another potential problem, not unique to S3, is due to Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS). CORS polices which routes and data are accesible from other origins. For example, a request from your SPA mysite.com to api.mysite.com is considered cross-origin, so it’s subject to CORS rules. Browsers enforce that cross-origin requests are only permitted when the server at api.mysite.com sets headers explicitly allowing them.

Even when you have control of the server, CORS headers can be tricky to set up correctly. Some SPA tutorials recommend side-stepping the problem using webpack-dev-server’s proxy setting. In this configuration, webpack-dev-server accepts requests to /api/* (or some other prefix) and forwards them to a server (eg, http://localhost:5000). As far as the browser is concerned, your API is hosted on the same domain—not a cross-origin request at all.

Some browsers will also reject third-party cookies. If your API server is on a subdomain this can make it difficult to maintain a logged-in state, depending on your users’ browser settings. The same fix for CORS—proxying /api/* requests from mysite.com to api.mysite.com—would also make the browser see these as first-party cookies.

In production or staging environments, you wouldn’t be using webpack-dev-server, so you could see new issues due to CORS that didn’t happen on your local computer. We need a way to achieve similar proxy behavior that can stand up to a production load.

CloudFront enters, stage left

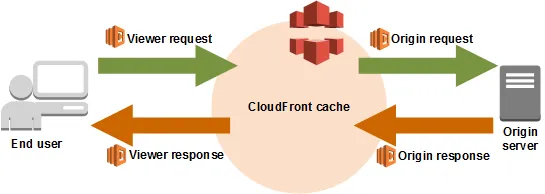

To solve these issues, I’ve found CloudFront to be an invaluable tool. CloudFront acts as a distributed cache and proxy layer. You make DNS records that resolve mysite.com to something.CloudFront.net. A CloudFront distribution accepts requests and forwards them to another origin you configure. It will cache the responses from the origin (unless you tell it not to). For a SPA, the origin is just your S3 bucket.

In addition to providing caching, SSL, and automatic gzipping, CloudFront is a programmable cache. It gives us the tools to implement push-state client-side routing and to set up a proxy for your API requests to avoid CORS problems.

Client-side routing

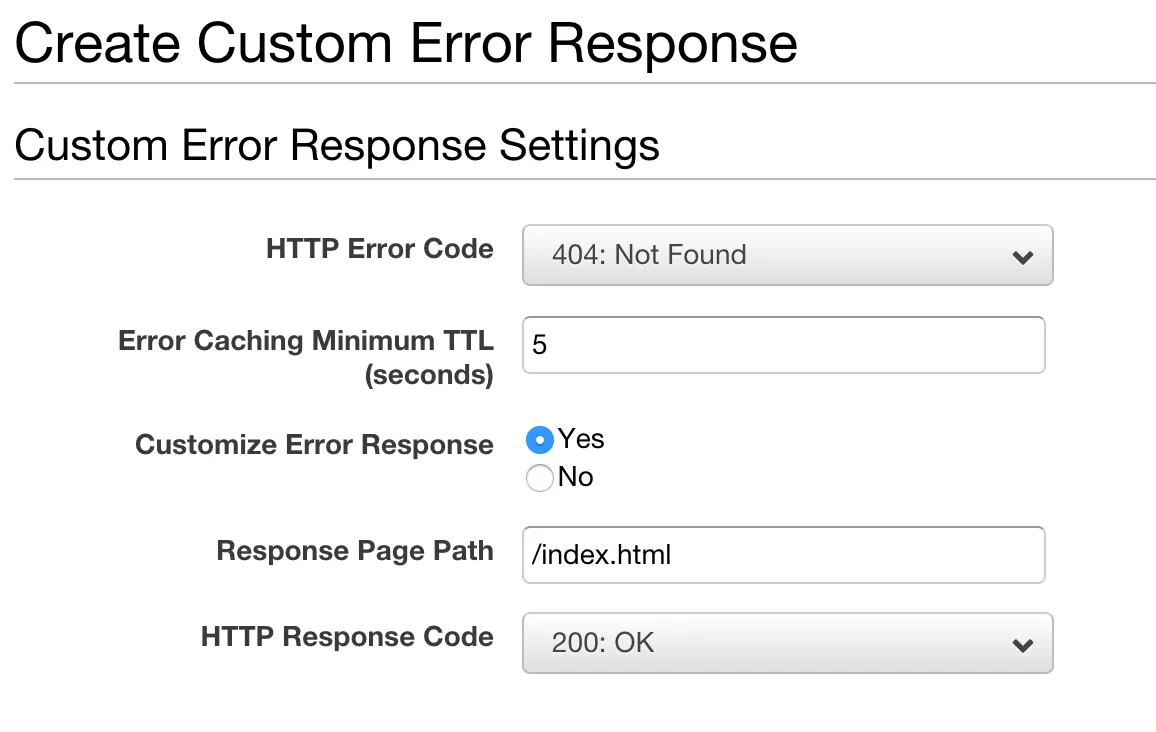

There are many suggestions to use CloudFront’s “Custom Error Response” feature in order to achieve pretty push-state-style URLs. When CloudFront receives a request to /login it will dutifully forward that request to your S3 origin. S3, remember, knows nothing about any file called login so it responds with a 404. With a Custom Error Response, CloudFront can be configured to transform that 404 NOT FOUND into a 200 OK where the content is from index.html. That’s exactly what we need for client-side routing!

The Custom Error Response method works well, but it has a drawback. It turns all 404s into 200s with index.html for the body. That isn’t a problem yet, but we’re about to set up our API so it is accessible at mysite.com/api/* (in the next section). It can cause some confusing bugs if your API’s 404 responses are being silently rewritten into 200s with an HTML body!

If you don’t need to talk to any APIs or don’t care to side-step the CORS issues by proxying /api/* to another server, the Custom Error Response method is simpler to set up. Otherwise, we can use Lambda@Edge to rewrite our URLs instead.

Lambda@Edge gives us hooks where we can step in and change the behavior of the CloudFront distribution. The one we’ll need is “Origin Request”, which fires when a request is about to be sent to the S3 origin.

We’ll make some assumptions about the routes in our SPA.

- Any request with an extension (eg,

styles/app.css,vendor.js, orimgs/logo.png) is an asset and not a client-side route. That means it’s actually backed by a file in S3. - A request without an extension is a SPA client-side route path. That means we should respond with the content from

index.html.

If those assumptions aren’t true for your app, you’ll need to adjust the code in the Lambda accordingly. For the rest of us, we can write a lambda to say “If the request doesn’t have an extension, rewrite it to go to index.html instead”. Here it is in Node.js:

const path = require("path");

exports.handler = (evt, ctx, cb) => {

const { request } = evt.Records[0].cf;

if (!path.extname(request.uri)) {

request.uri = "/index.html";

}

cb(null, request);

};

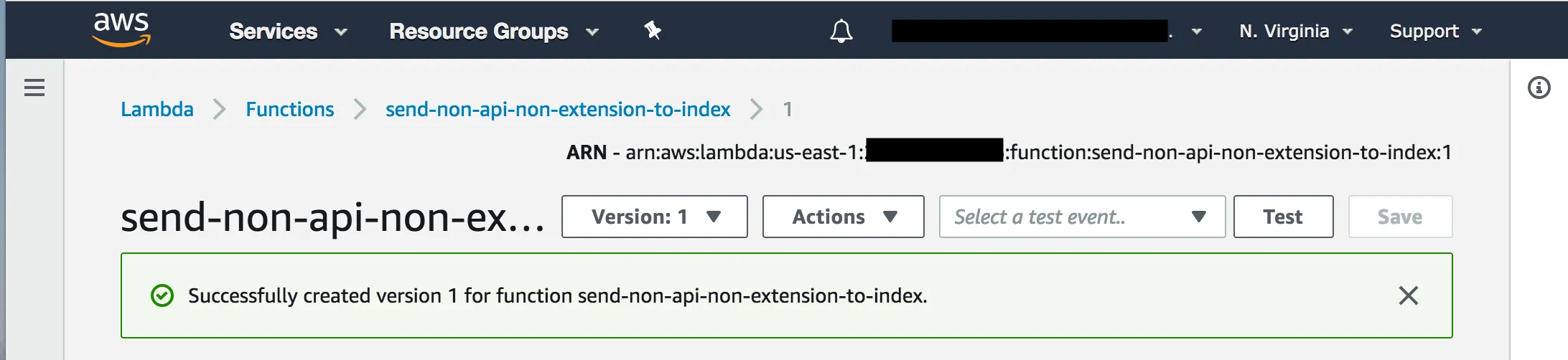

Make a new Node.js Lambda, and copy that code into it. At this time, in order to be used with CloudFront, your Lambda must be deployed to the us-east-1 region. Additionally, you’ll have to click “Publish a new version” on the Lambda page. An unpublished Lambda cannot be used with Lambda@Edge.

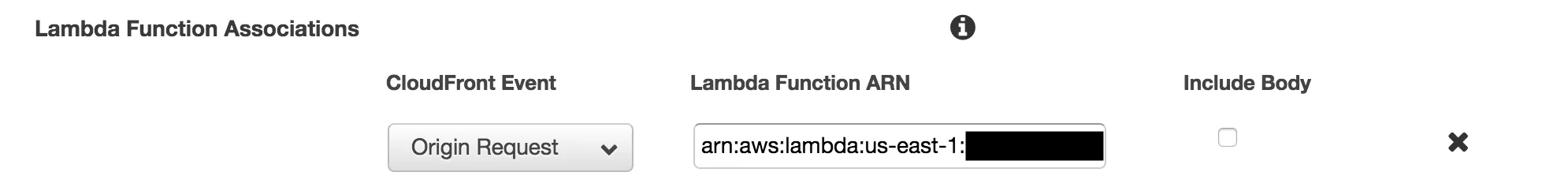

Copy the ARN at the top of the page and past it in the “Lambda function associations” section of your S3 origin’s Behavior. This is what tells CloudFront to call your Lambda when an Origin Request occurs.

Et Voila! You now have pretty SPA URLs for client-side routing.

Sidestep CORS Headaches

A single CloudFront “distribution” (that’s the name for the cache rules for a domain) can forward requests to multiple servers, which CloudFront calls “Origins”. So far, we only have one: the S3 bucket. In order to have CloudFront forward our API requests, we’ll add another origin that points at our API server.

Probably, you want to set up this origin with minimal or no caching. Be sure to forward all headers and cookies as well. We’re not really using any of CloudFront’s caching capabilities for the API server. Rather, we’re treating it like a reverse proxy.

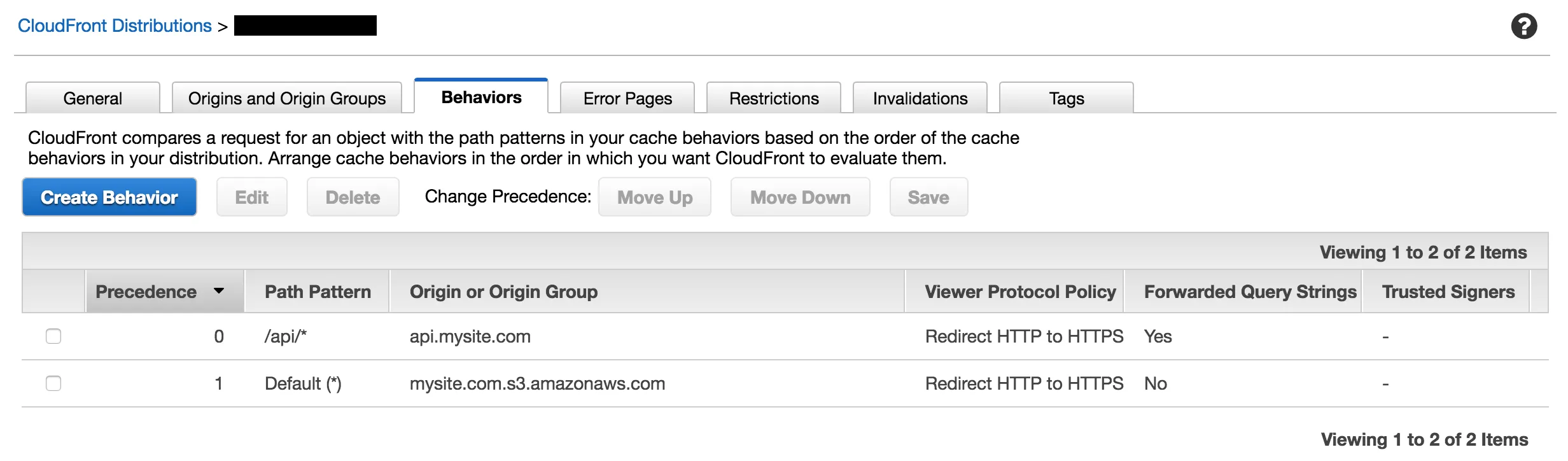

At this point you have two origins set up: the original one one for S3 and the new one for your API. Now we need to set up the “Behavior” for the distribution. This controls which origin responds to which path.

Choose /api/* as the Path Pattern to go to your API. All other requests will hit the S3 origin. If you need to communicate with multiple API servers, set up a different path prefix for each one.

CloudFront is now serving the same purpose as the webpack-dev-server proxy. Both frontend and API endpoints are available on the same mysite.com domain, so we’ll have zero issues with CORS.

Cache-busting on Deployment

The CloudFront cache makes our sites load faster, but it can cause problems too. When you deploy a new version of your site, the cache might continue to serve an old version for 10-20 minutes.

I like to include a step in my continuous integration deploy to bust the cache, ensuring that new versions of my asset files are picked up right away. Using the AWS CLI, this looks like

aws cloudfront create-invalidation --distribution-id $CLOUDFRONT_ID --paths '/*'